After four years of negotiations at the WTO, a “stabilised text” for the WTO Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) on e-commerce was released in July. This is a text now broadly agreed upon within negotiations, although there may be further minor adjustments to reach a final text.

The JSI is one of the most important negotiations because it would be a globally binding agreement in the area of e-commerce/digital trade, and incorporate a large number of countries into such an agreement for the first time.

Previously, we looked at the earlier texts and politics of the JSI: the controversial “plurilateral” structure of the agreement, the refusal of some large developing countries to join the JSI and the potential politics of future implementation within the WTO. As other commentators of the latest JSI release have observed, these points still stand.

Here we want to examine the content more closely. Now that a nearly final text is available, it is possible to dig deeper to examine what has been agreed upon and its implications.

JSI content

Broadly, we can say that the ambition of the JSI is quite modest. There are still some controversial areas (as discussed in the next section) but many of the more decisive aspects of digital trade are not present in this final draft. For instance, rules common in bilateral and regional agreements on cross-border data flows and data localisation are not present.

According to negotiators, one of the main reasons for this is that, frankly, powerful countries are still quite divided on their positions on these big topics. The JSI include diverse regional powers such as the US, EU and China as well as large emerging countries such as Brazil and Indonesia with varying views. Early on, negotiators had already started to talk about a first stage “quick deal” for the JSI which captured the “low-hanging fruit”. Only when this is done will they move on to more challenging issues within future agreements.

This strategy was cemented a year ago when the US changed its position in the JSI. It stepped back from examining data and source code “..to provide enough policy space for those debates to unfold”. With the US not negotiating such issues, it was not viable for them to be incorporated into the agreement at this point in time.

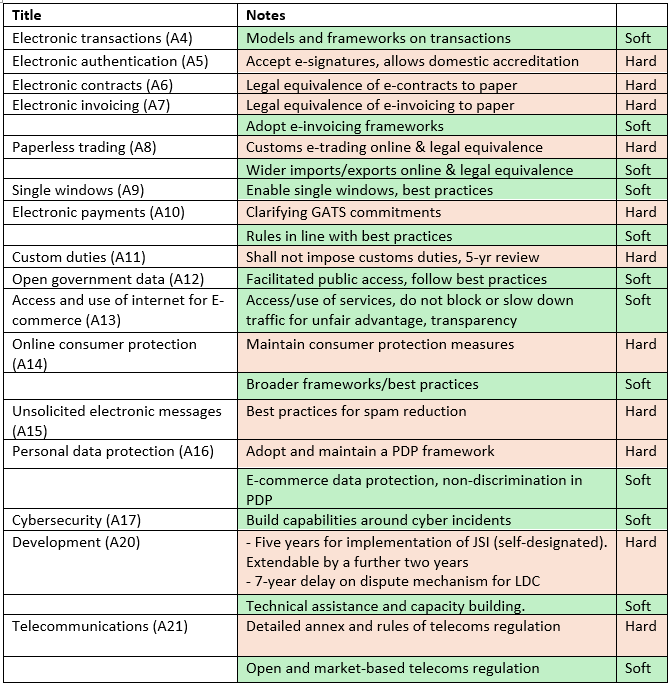

The agreement content (see table below) might then be described as focussing on establishing more foundational rules – encouraging members to become more standardised in areas such as online transactions, authentication, e-contracts and e-invoicing as well as installing effective regulation in areas such as consumer protection and data protection.

Much of the JSI text is written in “soft” rather than “hard” law (as shown in the table). This means that rules are not formally binding within law. Rather countries “endeavour to follow.” or “recognise the importance of..” specific rules. Agreeing to such softer rules can lead to momentum and may push political pressure from change, but provides more flexibility.

Even if these rules might then appear to be “low hanging fruit” and with flexibility, a significant number of JSI members have chosen not to be associated with the stabilised text. This includes Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Indonesia, Paraguay, Taiwan, Türkiye and the United States. This list includes a number of the more engaged developing countries in the negotiations and suggests issues still to be resolved.

Notable aspects of the agreement

Perhaps the most controversial component of the JSI text is the article on custom duties on electronic transmissions. The current bi-annual renewal of the temporary “Moratorium on custom duties on electronic transmissions” has become much debated in recent years. Some countries such as India have voiced their desire to end this rule, given the growing extent of digital goods in the economy and the long-term potential to cannibalise tax revenue.

The JSI makes this Moratorium more permanent. Although the JSI includes a “five-year review” of the rule, this is different to the current temporary moratorium which simply ends if WTO members do not agree to renew it at every WTO Ministerial meeting. This more permanent commitment to not implementing customs duties will be controversial to many. Likely, it is the reason for several of the non-signatories.

A second component of interest in the JSI is a long article on telecommunication regulation, including an annex on this topic. As commented in the earlier post, the presence of this in the agreement is an oddity. It is something that is already part of other agreements (GATS and telecoms agreements) and somewhat different to the broader digital trade discussion in the JSI. The justification made for this would be that digital trade requires sound telecom regulation as a foundation. But it feels out of place compared to the focus of the agreement.

For those who have signed the WTO “Telecom reference” paper previously, this inclusion might be uncontroversial – a rewording and extension of best practices in telecoms. But others have only partially agreed to the telecoms reference paper. For example, Thailand is an advocate of digital trade but in telecoms has included several exceptions and modifications in its GATS schedules. For such countries, agreeing to telecoms reform by the backdoor then is quite a significant step.

Beyond these two aspects, other articles allude to how such rules may limit policy space around emerging technologies. For example, does the binding text that countries “cannot prohibit parties from determining” e-authentication methods (A6) cause issues with Digital Public Infrastructure being implemented? Does the binding text granting public e-payment access to domestic payment and clearing systems (A10) limit important policy space in regulating central bank digital currencies (CBDC) in Asia? Such questions would require further technical analysis but suggest invisible dangers exist in even more innocuous rules.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the new aspect included in this agreement. A new exception called a personal data protection exception is present. In previous digital trade agreements, these exceptions tended to be highlighted within specific rules (such as those around free flows of data). Clearly, these previous forms of exception did not go far enough for parties such as the EU, Brazil and China who have stronger personal data rules. This exception then more unambiguously highlights this across the agreement, even though data flow rules are not part of the current JSI draft.

Is the JSI a development-orientated agreement?

As emphasised in the preamble to the text, the convenors strongly position the JSI as a developmental-orientated agreement. It is “..set to benefit consumers and businesses involved in digital trade, especially MSMEs. It will also play a pivotal role in supporting digital transformation among participating members”. So it is worth examining what is included in the JSI text in this respect.

Article 20 provides a specific article on the development aspects. These outline soft rules around mechanisms for technical support and capacity building between more and less advanced nations. They provide more detail on the mechanisms than is usually covered. Nevertheless, it is difficult to assess the impact that this might have in terms of support and funding for implementation.

For developing countries (as defined by the UN), extensions can be taken up on specific provisions in the JSI, including a five-year implementation period, with a potential extra two-year extension. LDCs are also excluded from dispute settlement mechanisms for seven years, as are developing countries when they seek the implementation periods above.

Given that for the most part the rules are less rigorous, this provides relatively generous periods. However, unlike other agreements such as GATS and the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) which define more flexible endpoints, the JSI specifically expects convergence in rules once implementation periods are over. Latecomer countries considering domestic industrial policy and specific digital infrastructures may find this idea of convergence in all these areas as limiting to their future ambitions.

With debates on digital development increasingly entwined with sovereignty, another interesting clause is the one on indigenous peoples (A26). It mirrors an earlier “Treaty of Waitangi” exception pushed by New Zealand in the earlier DEPA agreement, which supports the ability of Māori to assert and maintain sovereignty. How this new flexibility translates in the digital sphere is still up for debate, but this highlights an important clause in potentially allowing for certain types of sovereignty and control that move away from the straightjacket of technology convergence.

Summary

Overall, a provocative summary of the JSI “stabilised” text is that it is an agreement to make a ban on customs duties on electronic transmissions more permanent, with a few extra add-ons! Certainly, in comparison to other articles, this is the one which is more likely to make or break the inclusion of developing countries.

After earlier drafts, the inclusion of considerations of development has grown in this version, although some might still see these as limited – they hold hidden risks to “policy space” in terms of emerging technology and those who seek diverging technological pathways in the long term.

Beyond the content, as we discussed elsewhere – we need to admit the JSI is much more than its content, and whether this agreement can be done or not will be dependent on the broader politics that face the WTO as it moves forward.